The unfortunate coincidence of sharing their year of birth with Charles Dickens (and the centenary of the Titanic disaster) means that two other bicentenarians are being overlooked this year, both of them famous poets, albeit of very different sorts. However, do not despair - they have not been entirely forgotten.

The first is Edward Lear (1812-1888) who, although an ornithological draughtsman and painter, is best remembered for his nonsense verse, not least 'The Owl and the Pussycat'. Lear is commemorated in an exhibition by forty contemporary artists, showing images inspired by his work, at the Poetry Café in Covent Garden which opens on 7th May and closes 8th June 2012. (Free entry)

The second is Robert Browning (1812-1889), the rather intense Victorian poet whose most accessible piece is probably 'The Pied Piper of Hamelin'. As part of ongoing celebrations by the Browning Society, there will be a Commemorative Evensong at St. Marylebone Parish Church on Sunday May 13th at 5pm, with a wine reception afterwards. Professor Margaret Reynolds will talk about Browning's work, there will be a poetry reading, and a specially commissioned anthem based on Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s sonnet, “How Do I Love Thee”, sung by the church choir. (Free entry)

Interestingly, both 'The Owl and the Pussycat' and 'The Pied Piper of Hamelin' were both written for the sick children of friends of the respective poets - are there any other famous Victorian poems penned under similar circumstances?

Sunday, 29 April 2012

Tuesday, 24 April 2012

London Fonts

I know nothing about typography, but I keep wondering about the fonts of London street signs. This one appears to be Westminster's modern standard:

This one, similar but not identical (eg. compare the C), can be found in Camden:

This might be similar to the above but the 'O' looks fatter above?

This one seems similar but it's much blockier and look at the 'S':

And there are many other fonts out there, once you start looking - like this one with another distinctive 'C':

And this rare bold, older one (note it's WC not WC1 or WC2), with a similar 'C' but very different 'R'

This is from a similar period, perhaps, but a different 'R'

This one's very nice and unusual:

This spindly effort is great, presumably utterly unreadable at any distance:

I came across this one today - when does it date from, I wonder?

I'm sure there are many more, but my first question is - can anyone identify these fonts?

[UPDATE: A Twitter acquaintance suggests 'Folio' for the Westminster font - plausible?

https://twitter.com/#!/mrplip/status/195050734356668416/photo/1

Another Twitter lead says Univers Condensend

http://www.identifont.com/similar?N8Y

Another Twitter lead says Univers Condensend

http://www.identifont.com/similar?N8Y

This one, similar but not identical (eg. compare the C), can be found in Camden:

This might be similar to the above but the 'O' looks fatter above?

This one seems similar but it's much blockier and look at the 'S':

And there are many other fonts out there, once you start looking - like this one with another distinctive 'C':

And this rare bold, older one (note it's WC not WC1 or WC2), with a similar 'C' but very different 'R'

This is from a similar period, perhaps, but a different 'R'

This one's very nice and unusual:

This spindly effort is great, presumably utterly unreadable at any distance:

I came across this one today - when does it date from, I wonder?

I'm sure there are many more, but my first question is - can anyone identify these fonts?

Saturday, 21 April 2012

I Just Fell Off My Bike

Taking the family on a Dickens walk today (no, really), we were accosted on Newman Street - not far from the reprieved Cleveland Street Workhouse, and Charles Dickens' teenage home, opposite the former Middlesex Hospital - by a Victorian gentleman, albeit in modern guise.

His manner was polite and fairly engaging. He spoke unhurriedly but with a mildly pained expression.

'Excuse me,' he said, 'I'm sorry to trouble you, but I've just fallen off my bike, and I need to get to the A&E at Homerton Hospital. Look ...'

He rolled up the sleeve of his jackets- with remarkable ease, it must be said - and grimaced at the bloodied forearm beneath.

At least, it was certainly the colour and texture of dried blood; and one did not wish to enquire too closely.

A kinder soul might have offered to help; they might have rung 999, or if he was too proud to call an ambulance, they might have given him the money for the bus or taxi that would, plainly, be required.

At least, that was the idea.

For my part, I briskly directed him to the A&E of University College Hospital, a brisk five minutes' walk from the spot, rather than distant Homerton (some four or five miles distant, where, as it happens, my infant phenomenon was born). If I was made of sterner stuff, I might have added a few choice words. For I knew this gentleman, not in person, but from the works of Henry Mayhew, c.1861:

First, then, as to those having real or pretended sores. As I have said, there are few beggars of this class left. When the officers of the Mendicity Society first directed their attention to the suppression of this form of mendicancy, it was found that the great majority of those who exhibit sores were unmitigated impostors. In nearly all the cases investigated the sores did not proceed from natural causes, but were either wilfully produced or simulated. A few had lacerated their flesh in reality; but the majority had resorted to the less painful operation known as the "Scaldrum Dodge." This consists in covering a portion of the leg or arm with soap to the thickness of a plaister, and then saturating the whole with vinegar. The vinegar causes the soap to blister and assume a festering appearance, and thus the passer-by is led to believe that the beggar is suffering from a real sore. So well does this simple device simulate a sore that the deception is not to be detected even by close inspection. The "Scaldrum Dodge" is a trick of very recent introduction among the London beggars. It is a concomitant of the advance of science and the progress of the art of adulteration. It came in with penny postage, daguerreotypes, and other modern innovations of a like description.

The clues, of course, were in the question. Why would someone want to go several miles across London to Homerton, if they had just fallen off their bike? Fine, perhaps they lived in Hackney, like myself. But why would a recently bloodied wound be concealed by a pristine (and quite smart) jacket? And why on the upper part of the forearm - easily displayed to the general public - with no injury to the head or face? I'm no expert, but it didn't look like an injury from falling off a bike.

Yet, of course, some doubt remained. It smacked of the scaldrum dodge, yet would anyone really go to that trouble, in this day and age, just to scam a bus fare?

Naturally, the internet provides the answer ... apparently the scaldrum dodger has moved from his habitual pitch of Bethnal Green. [click here for details]

Has he been moving round London these last few years?

Does he lacerate his arm, or is the 'blood' merely an artful concoction of his own making?

I now feel I really should have given him his 'bus fare', if only for recreating a Victorian experience in the heart of the metropolis. On the other hand, it is something of a cruel hoax, calculated to deplete one's trust in one's fellow man; so perhaps not.

I wonder, does anyone actually know this man?

If you have met the scaldrum dodger, I should like to hear from you.

His manner was polite and fairly engaging. He spoke unhurriedly but with a mildly pained expression.

'Excuse me,' he said, 'I'm sorry to trouble you, but I've just fallen off my bike, and I need to get to the A&E at Homerton Hospital. Look ...'

He rolled up the sleeve of his jackets- with remarkable ease, it must be said - and grimaced at the bloodied forearm beneath.

At least, it was certainly the colour and texture of dried blood; and one did not wish to enquire too closely.

A kinder soul might have offered to help; they might have rung 999, or if he was too proud to call an ambulance, they might have given him the money for the bus or taxi that would, plainly, be required.

At least, that was the idea.

For my part, I briskly directed him to the A&E of University College Hospital, a brisk five minutes' walk from the spot, rather than distant Homerton (some four or five miles distant, where, as it happens, my infant phenomenon was born). If I was made of sterner stuff, I might have added a few choice words. For I knew this gentleman, not in person, but from the works of Henry Mayhew, c.1861:

First, then, as to those having real or pretended sores. As I have said, there are few beggars of this class left. When the officers of the Mendicity Society first directed their attention to the suppression of this form of mendicancy, it was found that the great majority of those who exhibit sores were unmitigated impostors. In nearly all the cases investigated the sores did not proceed from natural causes, but were either wilfully produced or simulated. A few had lacerated their flesh in reality; but the majority had resorted to the less painful operation known as the "Scaldrum Dodge." This consists in covering a portion of the leg or arm with soap to the thickness of a plaister, and then saturating the whole with vinegar. The vinegar causes the soap to blister and assume a festering appearance, and thus the passer-by is led to believe that the beggar is suffering from a real sore. So well does this simple device simulate a sore that the deception is not to be detected even by close inspection. The "Scaldrum Dodge" is a trick of very recent introduction among the London beggars. It is a concomitant of the advance of science and the progress of the art of adulteration. It came in with penny postage, daguerreotypes, and other modern innovations of a like description.

The clues, of course, were in the question. Why would someone want to go several miles across London to Homerton, if they had just fallen off their bike? Fine, perhaps they lived in Hackney, like myself. But why would a recently bloodied wound be concealed by a pristine (and quite smart) jacket? And why on the upper part of the forearm - easily displayed to the general public - with no injury to the head or face? I'm no expert, but it didn't look like an injury from falling off a bike.

Yet, of course, some doubt remained. It smacked of the scaldrum dodge, yet would anyone really go to that trouble, in this day and age, just to scam a bus fare?

Naturally, the internet provides the answer ... apparently the scaldrum dodger has moved from his habitual pitch of Bethnal Green. [click here for details]

Has he been moving round London these last few years?

Does he lacerate his arm, or is the 'blood' merely an artful concoction of his own making?

I now feel I really should have given him his 'bus fare', if only for recreating a Victorian experience in the heart of the metropolis. On the other hand, it is something of a cruel hoax, calculated to deplete one's trust in one's fellow man; so perhaps not.

I wonder, does anyone actually know this man?

If you have met the scaldrum dodger, I should like to hear from you.

Thursday, 19 April 2012

Battersea Power Station - A Tragi-Comic History

If Battersea Power Station could speak, I have a feeling it would say 'fuck off, leave me alone, let me die in peace'. Few other buildings in London have been promised so much by developers and received so little. Like me, you probably have heard the occasional news report about the building and its environs and wondered exactly how it fell into 30 years of disuse. Well, wonder no more - I have compiled a timeline.

[much of this is garnered from The Times database, for which, much

thanks]

1929-1933 (completed 1935) The first part of the power station ('A' Station) constructed, design by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott,

of red telephone box fame.

1945-1953 (completed 1955) The second part of the power station ('B'

Station) constructed. Now with four chimneys, rather than the initial two. Hurrah!

1975 'A' station closed, as plant ages and becomes less cost effective. Boo!

1977 Battersea Power Plant appears on Pink Floyd album cover, Animals,

becoming instantly recognisable to millions worldwide.

1980 Michael Heseltine awards the building Grade II listed status. Hurrah!

Then, unfortunately, the

trouble begins.

1980 Proposals for re-using the

site as a 'design museum, exhibition and conference centre' to supplement the

V&A

1980 Michael Montague, chairman

of the English Tourist Board, prophetically declares that the site risks

becoming 'a building of outstanding uselessness'.

1980 Readers of the Times

propose fanciful suggestions for Battersea, including 'a nuclear power

station' 'a prison' 'old people's flatlets' and 'a church'.

1980 Save Britain's Heritage

put forward the idea of a sports centre and exhibition hall. 'Three sports

halls, 20 squash courts, an ice rink, target ranges and a host of other

facilities could be provided in the brick shell.'

1982 A feasibility study by

architect Martin Richardson proposes a vast indoor sports area, combined with

engineering museum, to supplement the Science Museum. Other ideas on the table

include 'a giant discotheque' (YES!) and, more boringly, an incineration

plant.

1983 The 'B' Station is fully

decommissioned. But appears in Monthy Python's The Meaning of Life.

1983 'Would not this 'cathedral

of power' make a most awe-inspiring mosque?' letter to The Times

1983 As theme park fever grips

the country, the owners of Alton Towers amusement park propose turning the site

into an 'English Disneyland', to be completed by 1986, winning a design

competition run by the Central Electricity Generating Board. The CEGB, in midst

of the recession are heavily influenced by the figure of 4,500 new jobs being

promised. Proposed hours for theme park are 10am-2am, with most of the

site undercover. There will be 'theme shopping' although 'not Tesco's or

anything like that' and a Thames walkway. The turbine hall will be themed to

look like 'pre-industrial London' (shades of Dickens World?).

Also a 'haunted theatre' and 'futuristic shows'. Sounds impressive, eh? Wait,

there's more ...

1984 Further details of the

park include 'a gondola ride, taking people around 60 animated tableaux with

17,000 animated figures illustrating the British Empire. (YES!) The £4.50

admission fee, with no reduction for children, will cover all the attractions.'

1984 'Why does nobody suggest a

cathedral?' letter to The Times

1984 mention of possibility of

using grounds of Battersea site as coach park

1985 We learn the design in the

hands of the promising-sounding 'Texas-based Leisure and Recreation Concepts'.

Residents groups prophetically 'see the whole enterprise as foreign venture

capitalism, whose end product will be of doubtful local benefit'.

1986 More rides mentioned,

including 'simulated rides on rollercoasters or in car chases, computerised golf

"played" on the world's top ten courses, a skating lake, a parachute drop, and a

magic room whose pivotal design enables it to roll over 360 degrees'. Also, an

appearance as a deserted mining colony in Aliens. This is because the

site looks like, yes, a deserted mining colony.

1987 'Opening 1990'.

Yes, good luck with that.

1988 Mrs. Thatcher appears on

site, 'armed with the biggest laser-gun in Britain' (a terrifying prospect, if

ever there was) designed to trigger a sound and light show, heralding the new

theme park. Unfortunately the bangs are too loud. Residents ring 999, summoning

most of South London's emergency services to the scene. Proposals for naming the

theme park include 'Tower Inferno' (bit too ominous) 'Battersea Powerhouse' (so

80s!) and 'South Chelsea Fun Palace' (YES!) but boringly they go with

'Battersea, London'. Kudos to that copywriter. Mr. Broome, the head of the

Alton-Towers-related property group behind the project, promises 4,500 jobs (see

1983; nothing like consistency, eh?) and that the site will open on '2.30pm

on May 21, 1990'. Again, good luck with that.

1988 Redevelopment costs soar

from mere tens of millions to £230 million. Works stops, with the plant lacking

a roof or west wall. Awkward. Local campaigners realise that bulldozing the

'derelict' structure looking an increasingly profitable option for the

developer.

1989 Mr. Broome raises

suspicions by proposing 'four 17-storey office blocks, two 13 storey hotels, and

commercial premises around the power station'. With no mention of

roller-coasters or haunted mansions.

1989 The mystery deepens as

Broome enters into discussions with neighbouring property developer at Battersea

Wharf, for a joint project involving '2 million square feet of offices, 650,000

sq ft of conference facilities and two hotels on the site' whilst a new planning

application for the station includes use as a construction industry exhibition

and trade centre. A little ironic, as Broome's builders have not been paid in

several months.

1990 May 21 2.30pm

Journalists gathered dutifully on the vacant lot, in order to take the piss. A

Times report notes 'there is talk locally of it being converted into a

mosque' whilst The Battersea Power Station Community Group suggests 'residential

area, sporting and recreation areas, a museum and industrial workshops'. And the

kitchen sink.

1990 Broome's company is sued

for £175,000 in unpaid planning fees. Not altogether a good sign.

1991 Property company Park

Securities, owner of the site, falls into receivership. Minor problems with the

building include asbestos, sulphur penetration of brickwork (all 80 million of

them), subsidence and poor foundations built on clay. Local action group note

that it's very easy to wander in and nick stuff from the Art Deco interiors. And

people do.

1992 The site is bought by Hong

Kong property-developers, the Hwangs, and their company Parkview, who will

surely be the station's ultimate saviours. Surely. The very 1990s alternative of

an eco-friendly incineration centre is not taken up.

1993 At least the wasteland

appears regularly in The Bill. Hurrah!

1994. 'After 18 months of

ownership, the [Hwang] brothers and their company, Parkview International, have

done little or nothing to protect the exposed fabric of the power station from

the elements' Battersea Power Station Community Group

1995 The site looks the best it

has in years, in Richard III. Unfortunately it is 90% CGI.

1996 Don't panic. Something

will definitely happen. Because Andrew Lloyd Webber is on board. He will create

a theatre. There will also be a leisure and shopping complex which is gradually

being planned by architects. Very gradually. There will also be a '37 screen

multiplex cinema' (also, very 1990s). Other investors include BAA and the US's

Gordon Group.

1996 'It turns out there will

also be an art gallery. Also, erm, did we mention it, a 50 storey-high tower.'

No-one likes the tower, least of all English Heritage. The tower goes. Wait,

there's more: 'a media city, with film and television studios' and '32 cinemas'

(down from the 37 of earlier in the year, but not bad). The main thing is, they

have a plan now. A clear plan. There were also be a roller-blading rink, because

'inline skating is the fastest growing sport in the world'. Or, at least, it was

in 1996.

1996 Wandsworth planners by

this stage are desperate and will back almost anything, including 'a theatre, a

shopping centre, at least ten themed restaurants, a "discovery zone" for

children, and a ride up one of the chimneys.' Seriously. We learn that 'Two of

the chimneys will be converted into rides, one leisurely and one rocket-like'.

Whoooosh.

1996 The Prince of Wales

supports plans for a 10,000 seat ecumenical church on the adjoining land. No-one

notices. Instead, it will be an 'Autodome' celebrating car history. No-one bothers to build it.

1997 Woo-hoo. Warner Brothers

are involved in the cinema project. It will open '24 hours a day', or, in other

words, two showings of Titanic. The site becomes widely used by concert promotors for the best live bands and comedians. Also, Frank Skinner.

1998 One senior architect on

the project throws a hissy fit, when objections are raised to his 'Las

Vegas-style architecture'. We should be so lucky. It is noted that 'The 500

million scheme to include hotels, theme restaurants, and a 32 screen cinema

complex already has outline planning permission and will open in the year

2001'. Yeah, good luck with that.

1998 Article confidently

predicts that in 2003, the cinema complex with open, with - cough - 25 screens.

Yeah, good luck with that.

1999 The National Grid is

desolated to discover it owns some of the land at Battersea, which is 'worth' at

least 5 million pounds. It suggests that actually it's bound to want to build

another generating station in future, and might want a couple of quid more.

The architects are 'asked to stop work' while this is resolved. They stop, but

no-one notices.

1999 The land is sold. The

project 'could then be open and trading by 2004'. Note the word 'could'.

2000 Terence Conran suggests

the power station be used as a design centre. He has been in suspended isolation

in Chelsea since 1980 (see above).

2000 But there's good news.

Battersea will be the home of the Cirque du Soleil. Send in the clowns.

2002 Lend Lease, an Australian

property company, also involved in redeveloping the Dome, lends a hand - 'a sign

that the Hwang family is finally ready to develop the 35 acre site nearly ten

years after it first bought a stake in it'. The site will include a home for

Cirque du Soleil, a cinema, offices, shops, hotels and flats' and a river jetty.

Woo.

2003 After ten years of hard

draughting, full architects plans appear. 'A site transformed with green open

spaces, hotels and housing, complete with a new bridge across the Thames [YES!] ...

inside the giant turbine halls ... shops, bars, cinemas and restaurants. joined

by a series of walkways ... reborn at a cost of £800 million ... a 50 room hotel

on the roof ... a one-table restaurant seating 12 in a glass box on top of one

of the chimneys ... an entertainment and retail complex ... an open area whose

walls, ceiling, and floors can be moved to create tailor-made venues for any

event, from pop concerts to fashion shows'. Sadly, no clowns. But possibly two

Hyatt hotels. Unfortunately, the project will now cost £800 million, but what

are you going to do, eh? The one table restaurant is immediately fully booked until 2043.

2004 IKEA consider Battersea

but decide it's a bit too congested for their Grôeflughers

and Snëhhgards.

2006 Councillors approve the last set of plans from the Hwangs. ''They have

told us they will be ready to start work in earnest in the new year - we expect

them to keep to this,' says one very very trusting councillor.

2006 One month later, the

Hwangs sell the site for £400, a couple of hundred million profit, to Treasury

Holdings/Real Estate Opportunities. The latter has plans. Big plans - 'retail,

leisure, hotels, offices and residential spaces' - sound familiar?

2008 Plans for the new site

including running on biofuels (very 00s), homes, shops, parks, offices - look,

we'll build something. No, really.

2009 The site will definitely

include '3,700 homes built alongside offices, shops and restaurants on the site

by the River Thames in south-west London.' No, honest.

2010 Wandsworth Council approve

the latest plan. And why not? Let's face it, they've had thirty years of

practice. Green energy. New tube stations. Cyclists. Affordable housing. A

conference centre. 'London's biggest ballroom', presumably because Strictly

Come Dancing was on the telly at home when the architect was sketching. (cf. roller-blading, see 1996). Also, a riverbus. Woo.

2011 Utterly unpredictably, the

company managing the project falls into administration. Woops. They only have £502

million of debts, mind you; so it will soon be sorted. Nothing to see here.

2012 Battersea Power Station is

offered for sale - for the first time - on the open market. Any offers? Don't

all rush at once.

Tuesday, 17 April 2012

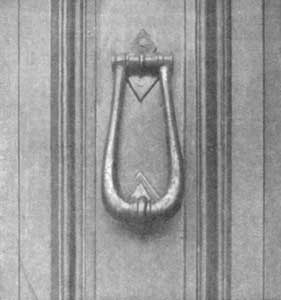

Famous London Door Knockers

[found on Google books, from the Harmsworth Magazine, 1898/99]

What souvenir of a great man can compete with the knocker of his door? A

door-knocker is to a man's house what a sign is to a shop or tavern; but

it is also something more. Take, for instance, the knocker on the door

of the official residence of the Prime Minister, No. 10, Downing Street.

No less a person than Lord Beaconsfield once described to a friend this

particular knocker as having a marked resemblance to the features of his

political opponent, Mr. Gladstone. There is no knocker in existence, we

may fairly state, that has been handled by so many distinguished people

as this one. If only the friends of Mr. Gladstone were enumerated, they

would make up a long list of illustrious names, and many Prime Ministers

have resided at the unpretentious, old-fashioned mansion so conveniently

situated for the Houses of Parliament.

It is to be wished that the Duke would follow up his artistic success in

this particular by designing a wall for Devonshire House to replace the

existing hideous structure.

Dickens' door-knocker recalls the residence of the happy couple who

removed to Doughty Street from Furnival's Inn shortly after their

marriage. It was here that Charles Dickens the younger was born, and

where the author of "Pickwick" first became on terms of friendship with

many of the brilliant men of letters of his day. The knocker is held in

its place by a fleur-de-lis of the same metal, and it was Serjeant

Talfourd who humorously rallied Dickens on his supposed predilection for

the French, who at that time were in the midst of preparing that series

of more or less revolutionary movements which preceded the downfall of

Louis Philippe and the ascendency of the third Napoleon.

But an older and more characteristic door-knocker may be found well

within a mile of Doughty Street, still on the door of a house once

inhabited by the great sage Dr. Samuel Johnson himself. Surely if any

knocker is characteristic of its owner this one is. It represents a

sturdy fist clenching a baton from which depends a bulky wreath of

laurel fastened in the middle by a lion's head. The worthy doctor, as we

are told by Boswell, carried no key, nor did he permit any member of his

oddly-selected household to possess one. At all times and seasons the

house in Bolt Court was inhabited, and unquestionably the burly knocker

resounded in the ears of the inhabitants of the court often enough, and

at unseemly hours, for the sage was not at all scrupulous as to what

hours he kept, and many a time would talk irregularly on at the club

until some of his neighbours had serious thoughts of rising.

The contemporaries of the great caricaturist George Cruikshank during a

fruitful period of his life will gaze not without feelings of emotion on

the accompanying representation of the familiar knocker on his house in

the Hampstead Road.

It was Clarkson Stanfield who, calling upon his friend Cruikshank one day, had much ado in making the artist's aged servant aware that a visitor awaited at the portals; again and again he knocked, but in vain; the servant's deafness was proof against the onslaughts of a vigorous if not wholly artistic door implement. At last, losing all patience, he picked up the foot-scraper and was about to impetuously hammer away at the panels, when the caricaturist, hastily throwing up an upper window sash, recognised and appeased his indignant visitor.

"You should," remarked Stanfield, "get a younger servant, or a heavier knocker, or else build your house in Turkish fashion—that is, without doors."

In every article which deals with the curiosities of London, the name of Dickens must figure very largely. The last knocker of our collection is the most remarkable one of all, inasmuch as Dickens derived his idea of Scrooge in "A Christmas Carol" from its hideous lineaments. Look at our photograph and then read Dickens' own description of the unamiable Scrooge:

"Oh! but he was a tight-fisted hand at the grindstone, Scrooge; a

squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old

Sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out

generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster.

The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose,

shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait.... He carried his own low

temperature always about with him; he iced his office in the dog-days;

and didn't thaw it one degree at Christmas."

|

| THE PRIME MINISTER'S (10, Downing Street, Westminster.) |

The knocker on the door of Carlyle's house, Cheyne Row, Chelsea, a house

which was occupied by him for half a century, is another very

interesting specimen. Scarcely was the young ex-schoolmaster and author

of "Sartor Resartus" well settled in his new abode than he began to

receive callers, who, if not very famous then, have since achieved

considerable renown.

Among them was young Mr. Charles Dickens, then the blushing "Boz," who,

with Mrs. Dickens, stepped out of a gorgeous green hackney coach to

administer a knock on the door, having driven all the way from Doughty

Street, Brunswick Square, to pay a call. Forster, Serjeant Talfourd,

Maclise, Macready, Landor, Leigh Hunt, and Thackeray were frequent

knockers during the first decade.

It is not difficult to imagine some youthful admirer of Carlyle giving a

timid knock at the door, and then wishing that he had the courage to run

away from the house before being ushered into the presence of the

irascible Philosopher. Mr. Alma Tadema's knocker is forbidding enough

in appearance, and holds out but little promise of the beauties of that

wonderful house where the artist resides in St. John's Wood. No doubt it

is, like everything else about his home, from a design by the great

painter himself.

The most beautiful knocker in this collection, if not the most beautiful in London, is that of the Duke of Devonshire, at No. 80, Piccadilly. It represents a head of classic contour set in a circular disc, chiselled with an exquisite border. Not a few among the Duke's guests have so far expressed their admiration of this work of art as to desire duplicates for themselves, but it is not known if any exist, it having been done by the Duke's own command from his own designs.

|

| THOMAS CARLYLE'S. (Cheyne Row, Chelsea.) |

|

| MR. ALMA TADEMA'S. (St. John's Wood.) |

|

| THE DUKE OF DEVONSHIRE'S. (Piccadilly.) |

The most beautiful knocker in this collection, if not the most beautiful in London, is that of the Duke of Devonshire, at No. 80, Piccadilly. It represents a head of classic contour set in a circular disc, chiselled with an exquisite border. Not a few among the Duke's guests have so far expressed their admiration of this work of art as to desire duplicates for themselves, but it is not known if any exist, it having been done by the Duke's own command from his own designs.

|

| CHARLES DICKENS'. (17, Doughty Street.) |

|

| DR. JOHNSON'S. (Bolt Court, Fleet Street.) |

|

| CRUIKSHANK'S. (Hampstead Road, N.W.) |

It was Clarkson Stanfield who, calling upon his friend Cruikshank one day, had much ado in making the artist's aged servant aware that a visitor awaited at the portals; again and again he knocked, but in vain; the servant's deafness was proof against the onslaughts of a vigorous if not wholly artistic door implement. At last, losing all patience, he picked up the foot-scraper and was about to impetuously hammer away at the panels, when the caricaturist, hastily throwing up an upper window sash, recognised and appeased his indignant visitor.

"You should," remarked Stanfield, "get a younger servant, or a heavier knocker, or else build your house in Turkish fashion—that is, without doors."

In every article which deals with the curiosities of London, the name of Dickens must figure very largely. The last knocker of our collection is the most remarkable one of all, inasmuch as Dickens derived his idea of Scrooge in "A Christmas Carol" from its hideous lineaments. Look at our photograph and then read Dickens' own description of the unamiable Scrooge:

|

| THE KNOCKER THAT SUGGESTED SCROOGE IN DICKENS' "CHRISTMAS CAROL." (8, Craven Street, Strand.) |

Sunday, 15 April 2012

Nights Out - Soho

Like many others, I have long been a fan of Professor Judith Walkowitz's City of Dreadful Delight (1992) which devotes chapters to, amongst other things, the Jack the Ripper murders, W.T.Stead's exposé of child trafficking, the 'Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon', and the Mrs. Weldon case (the woman who famously fought back against her conniving husband having her certified as a lunatic). That book presents a fascinating picture of women's lives in late Victorian London - I'd go so far as to say it is essential reading for anyone with even a passing interest in the era - and so it was with some excitement that I came to Walkowitz's new book Nights Out: Life in Cosmopolitan London which, despite the title, is actually a study of Soho.

The book begins with Mrs. Ormiston Chant's 1894 famous investigation of prostitutes at the Empire Music Hall in Leicester Square - finding women 'very much painted' (wearing make-up!) prowling the Empire's promenade, on the look out for male company. It moves on from the Victorian era to the Edwardians, focussing on Maud Allan's racy dance interpretation of 'Salome' which drew a new female audience to West End theatres. Some were girlishly adoring - I love the quote from a fan letter: 'I saw you and thought your dancing perfect. I tried to move my arms like yours, but they seemed to have much fewer joints'.

The heart of this book, however, is - for me at least - less familiar territory, namely Soho between the wars. We have the Soho of Italian restaurants, fascists and anti-fascists, anarchists, and - that Soho perennial - police corruption. The chapter on Berwick Street market is particularly illuminating and evocative - a piece of Soho that was (rather briefly) a Jewish enclave, selling cheap frocks and hosiery to shoppers who were daring enough to dip into the shady alleys behind Oxford Street, home both to 'flappers' searching for bargain frocks and the aggressive 'schleppers' (touts, both men and women) who attempted to lure passing trade into their shops. The section on dancing at the Astoria is equally gripping, with Walkowitz utilising oral history to great efect.

The book continues with a chapter on 1920s/30s night-clubs, the 'bottle parties' of the jazz age where the likes of the redoubtable Mrs. Meyrick opened clubs in Soho basements, negotiating with both corrupt policemen and criminal gangs, always bouncing back after arrest and imprisonment. Then, finally, a chapter on the Windmill Theatre, famous for its 'nude tableau', run by the eccentric Mrs. Henderson.

Overall, the book is a fabulous read and I would definitely recommend it to anyone with an interest in Soho or London between the wars. If pushed, I would level three criticisms. The first is simply inherent in the nature of the work - this is an academic book, and phrases like 'kinesthetic and social remappings' occasionally appear. For those of us not used to such language, it can be bewildering, but Walkowitz is a skilled author and the academic analysis never overwhelms the history (with the possible exception of the introduction, which the general reader may prefer to read after finishing the body of the work). Second, the time-frame is rather peculiar. I had hoped to see something on my own Soho favourite, Caldwells dancing-rooms - a dance-hall of the 1850s - or the infamous Argyle Rooms - or Soho in the 1960s - but all of these fall outside Walkowitz's period. Third, I did wonder whether the section on night-clubs was rather rushed, even if it was only intended to cover the career of Mrs. Meyrick. I would say, for instance, that I found Marek Kohn's Dope Girls a more interesting excursion into jazz-age London. The sum total of these complaints, I suppose, is that Walkowitz does not provide a complete history of either the period or the district - but, in fairness, she makes no claim to do so.

Perhaps Soho's night life is too vast a subject to be tamed by a single author. Yet, to level this sort of crticism feels churlish. For this reader, Nights Out brought to light many new aspects of London history and proved an engrossing read. I would say it is well worth both your time and money.

The book begins with Mrs. Ormiston Chant's 1894 famous investigation of prostitutes at the Empire Music Hall in Leicester Square - finding women 'very much painted' (wearing make-up!) prowling the Empire's promenade, on the look out for male company. It moves on from the Victorian era to the Edwardians, focussing on Maud Allan's racy dance interpretation of 'Salome' which drew a new female audience to West End theatres. Some were girlishly adoring - I love the quote from a fan letter: 'I saw you and thought your dancing perfect. I tried to move my arms like yours, but they seemed to have much fewer joints'.

The heart of this book, however, is - for me at least - less familiar territory, namely Soho between the wars. We have the Soho of Italian restaurants, fascists and anti-fascists, anarchists, and - that Soho perennial - police corruption. The chapter on Berwick Street market is particularly illuminating and evocative - a piece of Soho that was (rather briefly) a Jewish enclave, selling cheap frocks and hosiery to shoppers who were daring enough to dip into the shady alleys behind Oxford Street, home both to 'flappers' searching for bargain frocks and the aggressive 'schleppers' (touts, both men and women) who attempted to lure passing trade into their shops. The section on dancing at the Astoria is equally gripping, with Walkowitz utilising oral history to great efect.

The book continues with a chapter on 1920s/30s night-clubs, the 'bottle parties' of the jazz age where the likes of the redoubtable Mrs. Meyrick opened clubs in Soho basements, negotiating with both corrupt policemen and criminal gangs, always bouncing back after arrest and imprisonment. Then, finally, a chapter on the Windmill Theatre, famous for its 'nude tableau', run by the eccentric Mrs. Henderson.

Overall, the book is a fabulous read and I would definitely recommend it to anyone with an interest in Soho or London between the wars. If pushed, I would level three criticisms. The first is simply inherent in the nature of the work - this is an academic book, and phrases like 'kinesthetic and social remappings' occasionally appear. For those of us not used to such language, it can be bewildering, but Walkowitz is a skilled author and the academic analysis never overwhelms the history (with the possible exception of the introduction, which the general reader may prefer to read after finishing the body of the work). Second, the time-frame is rather peculiar. I had hoped to see something on my own Soho favourite, Caldwells dancing-rooms - a dance-hall of the 1850s - or the infamous Argyle Rooms - or Soho in the 1960s - but all of these fall outside Walkowitz's period. Third, I did wonder whether the section on night-clubs was rather rushed, even if it was only intended to cover the career of Mrs. Meyrick. I would say, for instance, that I found Marek Kohn's Dope Girls a more interesting excursion into jazz-age London. The sum total of these complaints, I suppose, is that Walkowitz does not provide a complete history of either the period or the district - but, in fairness, she makes no claim to do so.

Perhaps Soho's night life is too vast a subject to be tamed by a single author. Yet, to level this sort of crticism feels churlish. For this reader, Nights Out brought to light many new aspects of London history and proved an engrossing read. I would say it is well worth both your time and money.